I was teaching a class at the University of Manchester yesterday, and listening to the interpreting students tackle a piece of rapid, ‘real-life’ French reminded me of the days when I was a trainee on the SCIC stage, honing my own interpreting skills at the European Commission in Brussels.

At the time, I had three mentors – well, they were actually called godmothers and godfathers – and I vividly remember sitting in a dummy booth in the Borschette building, feeling totally inadequate as I tried to follow arcane customs negotiations and interpret into English under the watchful eye (and ears) of my vastly more experienced colleagues.

One of my mentors, twinkly-eyed and bearded, reminded me of a genial brown bear. He would doze off gently in the back of the booth, while the delegates’ German reached parts of my brain other languages cannot reach.

One day, my mentor hit me with these words of wisdom: ‘The problem with your German, Sophie, is that you don’t have a fourth gear’. My internal reaction to this pronouncement was ‘Ha ha ha, I’d be happy if I could even find second gear!’, but by then I had already learned that it was a bad idea to show weakness, so I didn’t say it out loud. This was one of the few times in life that I managed to keep my mouth shut instead of blurting out my innermost thoughts and putting my foot squarely in my mouth.

In class yesterday, I found myself repeating those words to the students. ‘When you’re dealing with fast and furious French like this, you need to be firing on all cylinders. You need to find fifth gear. You need to be 100% on the ball.’ And other such imagery.

Image my consternation when one of the students pointed out that this isn’t a very helpful comment. What does it actually mean to move into a higher gear, and how do you do it?

Huh.

It always rocks me back on my heels a little when I say something I think is fairly obvious, and it becomes apparent that it’s not that clear to everyone else. It’s a salutary reminder that our brains don’t all work the same. Or at least, that my brain doesn’t work like anyone else’s.

So I tried to unpack my own statement.

Shifting into a higher gear

What does it mean to shift into a higher gear?

To me, this phrase describes the difference between ambling along at 30 mph admiring the scenery out of the car window, versus zipping down the motorway at 70 mph (obviously, I’m so law-abiding I never break the speed limit…).

In the former case, you have plenty of time to react to hazards (dozy pedestrians, aggressive drivers, unexpected cyclists just around a bend, potholes, or where I live, hedgehogs). You can change course in time to avoid a collision. In interpreting terms, this equates to a reasonably slow, well structured speech, which allows you some time to think, adjust your décalage, tidy up the speaker, and reformulate into elegant English/Turkish/whatever your target language is.

When you’re driving much faster on the motorway, however, you have to react very quickly to anything new and/or dangerous and be hyper-aware of everything going on around you at all times (e.g. other drivers’ behaviour). In interpreting terms, this is where you have a crazy fast speaker throwing facts and figures at you (or quips, jokes, asides, interjections, examples…). If you take too long over your analysis or reformulating, there’s a good chance you’ll make a mistake or miss an idea (or possibly several sentences).

In other words, ‘fifth gear’ in simultaneous implies being able to deal successfully with fast, dense speech. And that, in turn, implies a faster reaction time.

So when I talk about fifth gear, firing on all cylinders, or being on the ball, I really mean that your reaction time needs to be super-sharp.

Knowing this is one thing. Doing it is another. How can you speed up your reaction time when interpreting in simultaneous mode?

Speeding up your reaction time

In order to react faster when faced with lots of information delivered quickly (possibly with the extra challenge of asides, in jokes, or cultural references thrown into the mix), you need to a) process and analyse the information faster, b) say it faster in your target language (i.e. get to the point), or c) both.

Spit it out

On the output side of the simultaneous equation, here are some techniques to try:

- Don’t repeat information. Say it once, and move on. If the point the speaker is making has been covered already during the speech, or can legitimately be subsumed in a slightly more general point, leave it out.

- Choose concise solutions in your target language. Good news for English As and retourists: English is generally a very concise language (see my blog post about making use of this feature, and others, to improve your interpreting).

- Use intonation strategically to make up for being less explicit. You can do a huge amount with your voice alone: highlight a specific point, indicate that you’re mentioning a secondary item of information, introduce a digression, link to the next part of the speech…

- Speak faster! I don’t generally advise my students to practise doing this, because it’s difficult to change your natural speech style, but I know other trainers who do.

Coincidentally, if you put all of this into practice, you will be saying less, and freeing up more space to listen to the speaker. If you think of your brain’s processing capacity during simultaneous interpreting as being a finite resource, freeing up some of that capacity by being more concise and streamlining your output should enable you to process what you hear better and faster.

Process faster

On the input side of the simultaneous equation (i.e. what you are hearing), there are also techniques you can apply to help you process (i.e. hear, understand, digest, edit) the information faster.

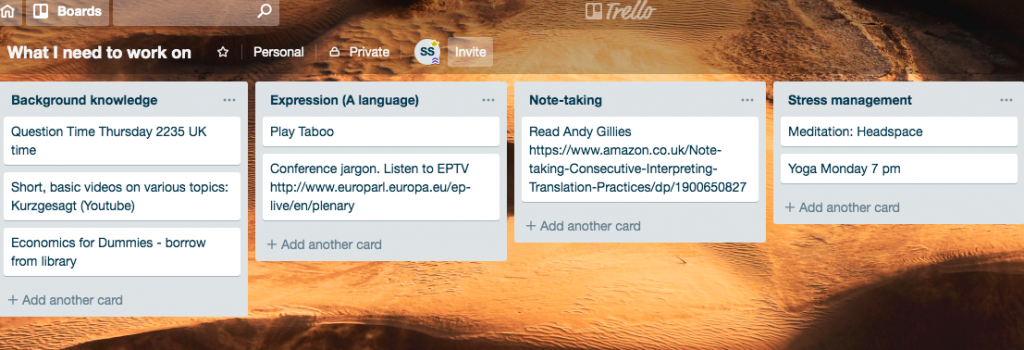

- Keep working on your source language comprehension, especially if it’s one of your C languages and not a B. Just trying to understand the original, especially if the syntax is convoluted, can burn up a lot of brain juice, leaving you much less for incisive analysis and good expression in the target language. So work hard on your comprehension.

- The same goes for cultural references in the source language. If you haven’t immersed yourself in the culture of the source language, you may completely miss some of the speaker’s references; or you may hear something, but not really understand what it relates to; or you may get it, or half-get it, but be unable to come up with a decent, brief explanation quickly enough.

- Ditto background knowledge. If you have a solid understanding of the issues involved, so that much of the material is familiar to you from the news or your prior experience in this field, you won’t have to work so hard to decipher what the speaker is saying. If you’re interpreting a panel debate about Brexit, and you don’t know much about the workings of the EU, British politics, or previous referendums, your work will be very much harder.

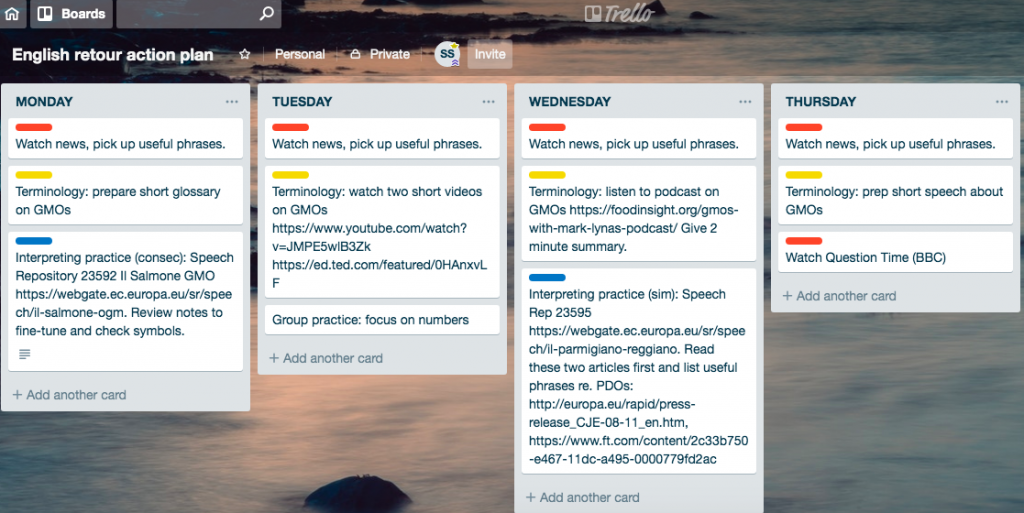

- Improve your reflexes. If you like sport, you will know how important muscle memory is to performance. Athletes, dancers and gymnasts (and professional musicians) go over the same movements over and over again, so that they can bypass their conscious brain in pressure situations and fall back on ingrained habits. Their body remembers what to do without having to think about it. When you’re interpreting, it’s really useful to have ready-made solutions for problems that come up again and again. In simple terms, this means practising frequently-occurring phrases – perhaps speech openings and closings, or typical comments from the Chairman of a meeting, especially in your B language – but also giving some thought to fragments and expressions that are characteristic of your source language. In French, for example, you don’t want to have to reinvent the wheel every time you encounter something like ‘langue de bois’, ‘sur la forme et sur le fond’, or ‘des pistes de réflexion’. So think about your options in advance, when you come across one of these ‘classics’ in a podcast or article, or when listening to the news.

Finally, when you’re dealing with a speaker who’s like greased lightning, it’s important to manage your décalage.

Although I usually urge my students not to stick too closely to the speaker (for fear of linguistic interference or of ending up facing a brick wall in simultaneous, leading to unfinished sentences or errors), most interpreters won’t be able to get all the information in if they leave a long décalage when dealing with very fast speech.

There is an argument, therefore, for not dilly-dallying, especially if the speaker is throwing out lots of figures. Your brain can’t retain them in the same way as it retains ideas, so stick close behind and get them out as quickly as possible (if the speech is very fast, writing down the figures and units will inevitably lead to a loss of other information). However, this is by no means an excuse for copying the syntax of the source language or slipping into ‘parrot’ mode, i.e. repeating what the speaker says without sufficient analysis. Even in a fast speech, there is room for analysis and reformulation. For me, the trick lies in hanging back a little when the next idea/sentence begins after a pause. If you don’t jump in straight away, you can decide which way you’re going to leap, and do some strategic shifting around of information. Elsewhere in the sentence, which may be very long, you may have less room for manoeuvre. This way, I have a better chance of beginning the sentence in an idiomatic way, and then I chop the rest of it up into manageable pieces (salami technique/chunking), so that I don’t get bogged down in long and complicated syntax.

A final point: if the speaker is very dense and factual, you really need to stay on top of him (or her). On the other hand, if the speaker delights in peppering the speech with asides, in jokes, cultural references, quotes, and the like, your priority must be, at all costs, to understand the main ideas. Sounds obvious, doesn’t it? And yet, with a rapid flow of information, it’s easy to lose sight of this most basic of principles. If you don’t catch the main ideas, the next two or three sentences you hear may be completely meaningless without their context. So if the speaker is shooting off in all directions, focus heavily on understanding the his or her intentions, and sacrifice some of the other fluff if necessary. Summarise where you can. Use intonation to convey the speaker’s tone if you don’t have time to do it in words.

I hope this post has given you some ideas for tackling difficult material successfully. If it sounds a little abstract, that’s because it’s difficult to talk about this sort of thing without illustrating your approach using an actual speech + interpreting performance. And that’s precisely what I propose to do in my next blog post.

For those with French, I’ll be talking about Jean Quatremer’s contribution as moderator of a debate about the Brexit referendum. Here’s the clip, in case you’d like to have a go at interpreting Quatremer’s introduction (or indeed, Emmanuel Macron’s contribution).

What are your best tips for dealing with speakers who go like the clappers?